Byssocorticium atrovirens (Fr.) Bondartsev & Singer

Basidiomycota: Agaricomycotina: Agaricomycetes: Atheliales: Byssocorticiaceae:![]() Byssocorticium

Byssocorticium![]()

![]()

Introduction

Blue is the rarest color in nature. So, why is this crust, hidden under branches and leaf debris, blue? Whatever the reason, the color has been preserved throughout the evolution of the genus — all seven recognized species of Byssocorticium are blue (Index Fungorum, accessed July 17, 2022).

Byssocorticium is a member of the family Byssocorticiaceae (along with Athelopsis and Leptosporomyces) in the poorly understood but ecologically dynamic order Atheliales, which consists entirely of crust fungi (Rosenthal et al. 2017, Sulistyo et al. 2020). The genus name derives from the byssoid, or cotton-like, texture of the basidiocarp. Telltale signs that you have a Byssocorticium species include a blue coloration, a byssoid or loose, felt-like texture, as well hyphae that branch at right angles.

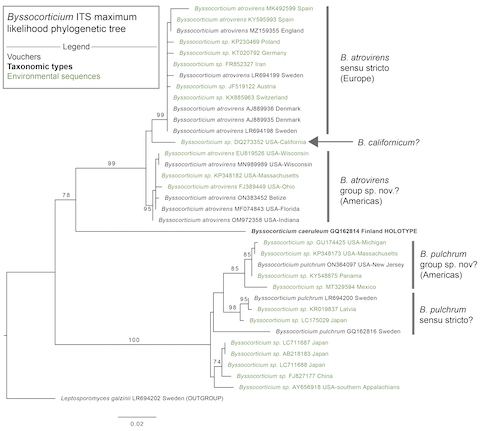

Byssocorticium atrovirens may be very widespread, but more likely most blue specimens are labelled as Byssocorticium atrovirens when they actually constitute different species. Sequence data suggest "B. atrovirens" specimens from the Americas constitute a distinct species from European B. atrovirens (see tree below). This specimen unexpectedly had finger-like hyphidia, a characteristic reported for Tretomyces lutescens — a yellow species that was once considered a member of Byssocorticium (Kotiranta et al. 2011, Sulistyo et al. 2020). It would be interesting if this character presented as a consistent morphological difference between the European and American clades. Further taxonomic investigations are needed to resolve the species boundaries in the B. atrovirens group.

Even though Byssocorticium atrovirens grows on the bottom of plant debris, it actually forms ectomycorrhizae (Tedersoo et al. 2010) and may play an important role in the functioning of forest ecosystems (Rosenthal et al. 2017).

Description

Ecology: The documented specimen was growing on the underside of deciduous leaf debris.

Basidiocarp: Effused, hymenial surface even, blue with yellowish patches, byssoid texture.

Chemical reactions: NA

Spore print: NA

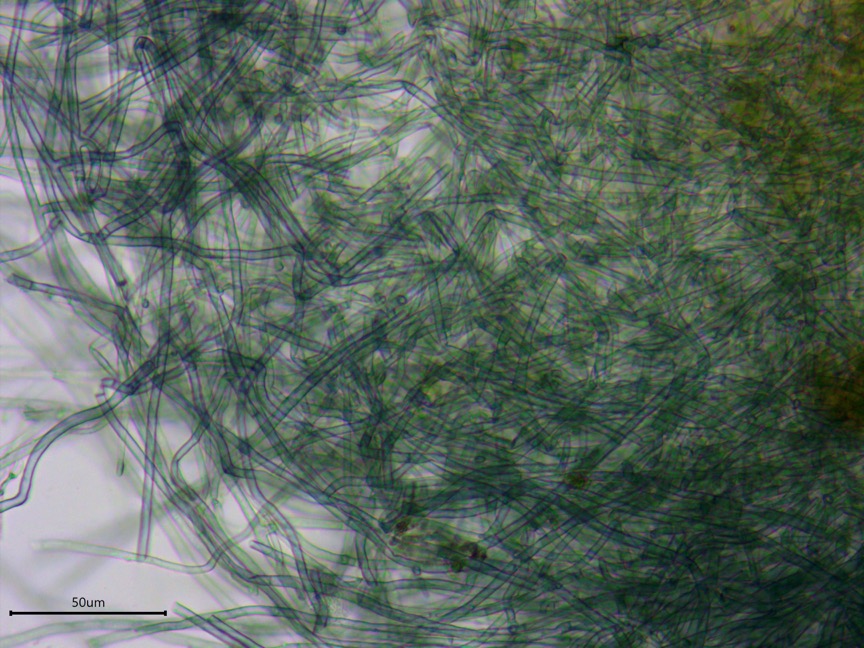

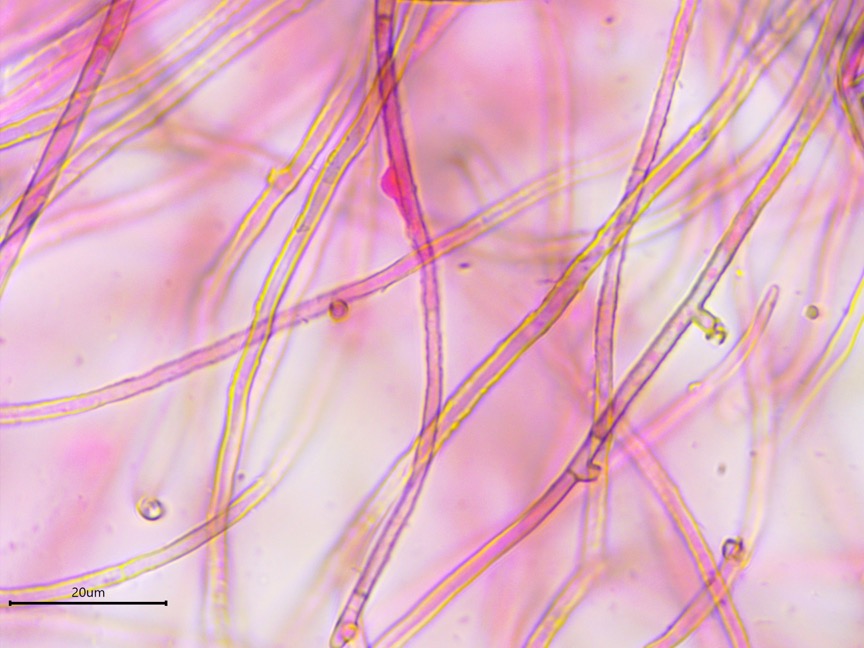

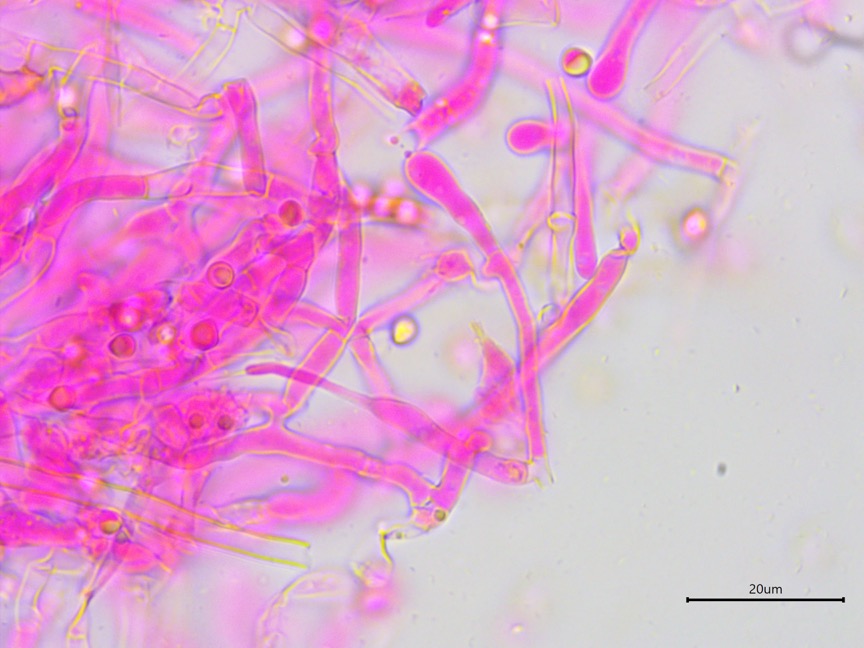

Hyphal system: Monomitic, blue-green, subicular hyphae with simple septa, 2.5–3.5 µm wide (n = 10), branching at right angles, with a coarse texture not dissolving in KOH.

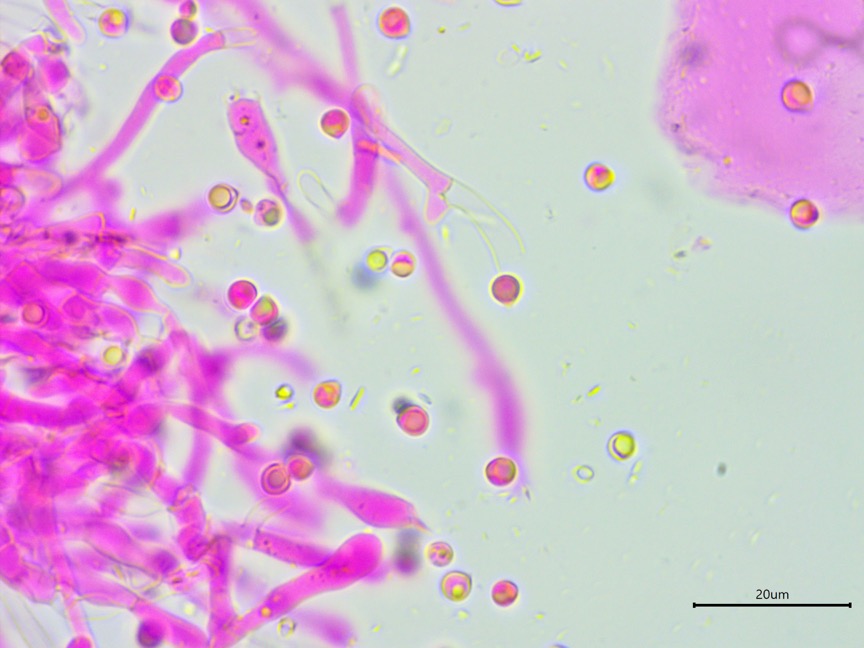

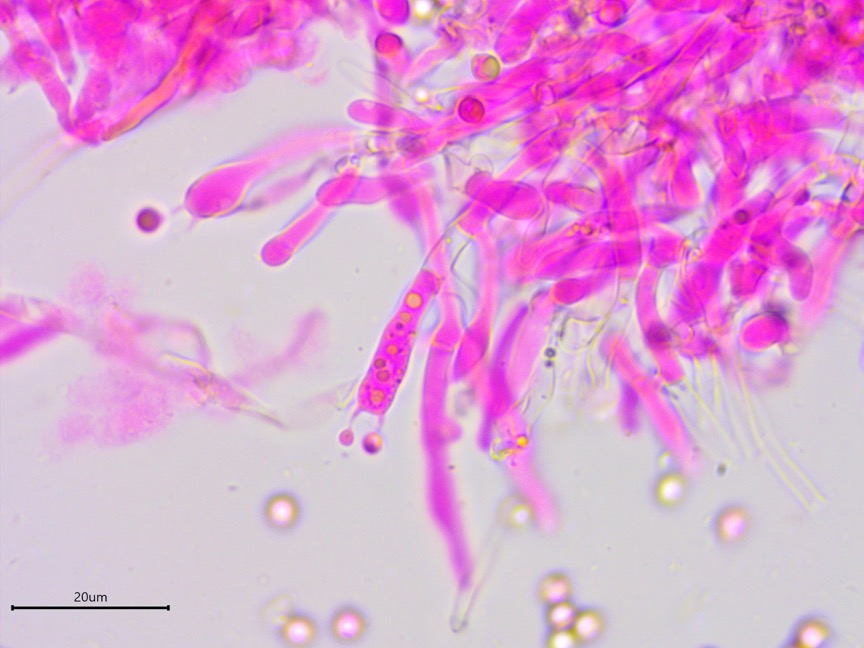

Basidia: Terminal, clavate, length (17.2) 17.7–20.6 (21.3) µm, width (3.7) 4.0–5.2 (5.4) µm, x̄ = 19.1 ✕ 4.6 µm (n = 10), with four sterigmata, length (1.1) 1.9–3.3 (5.4) µm, x̄ = 2.6 µm (n = 10), occasionally with a basal clamp, often filled with oil droplets.

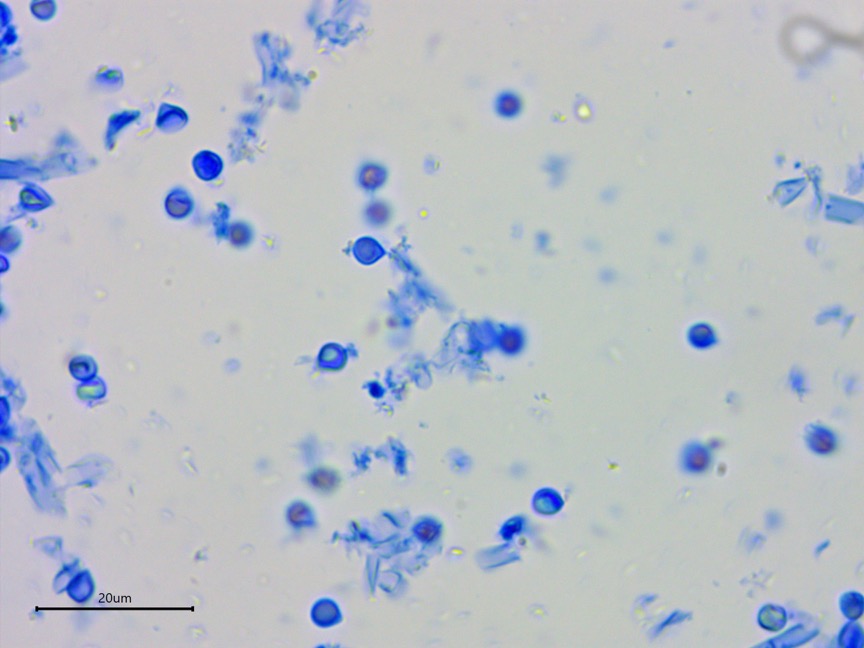

Basidiospores: Smooth, thick-walled, hyaline, inamyloid, cyanophilous cell wall, subglobose to broadly ellipsoid in form, pyriform in shape with a tapered apiculus; length (3.5) 3.8–4.4 (5.1) µm, width (3.2) 3.4–4.0 (4.4) µm, x̄ = 4.1 ✕ 3.7 µm, Q (1.0) 1.0–1.2 (1.4), usually with a single large guttule occupying 60–80% of the spore cytoplasm (n = 30).

Sterile structures: Cystidia absent, hyphidia finger-like, as in Tretomyces lutescens.

Sequences: ITS rDNA (MN989989).

Notes: All measurements were taken using a smash mount of dried tissue in 5% KOH stained with phloxine.

Specimens Analyzed

iNat17333142; 06 October 2018; 5304 Reeve Rd., Dane Co., WI, USA, 43.1458 -89.8114; leg. Stephen Russell, det. Alden Dirks, ref. Jülich & Stalpers (1980) and Bernicchia & Gorjón (2010); Kriebel Fungarium PUL00042321.

References

Bernicchia, A. & Gorjón, S.P. (2010). Fungi Europaei, Volume 12: Corticiaceae s.l. Massimo Candusso, Italia.

Jülich, W. & Stalpers, J. A. (1980). The Resupinate Non-poroid Aphyllophorales of the Temperate Northern Hemisphere. North-Holland Publishing Company, Amsterdam, Oxford, New York.

Kotiranta, H., Larsson, K.-H., Saarenoksa, R., & Kulju, M. (2011). Tretomyces gen. novum, Byssocorticium caeruleum sp. nova, and new combinations in Dendrothele and Pseudomerulius (Basidiomycota). Finnish Zoological and Botanical Publishing Board, 48(1), 37–48.

Rosenthal, L. M., Larsson, K.-H., Branco, S., Chung, J. A., Glassman, S. I., Liao, H.-L., … Bruns, T. D. (2017). Survey of corticioid fungi in North American pinaceous forests reveals hyperdiversity, underpopulated sequence databases, and species that are potentially ectomycorrhizal. Mycologia, 109(1), 115–127.

Sulistyo, B. P., Larsson, K.-H., Haelewaters, D., & Ryberg, M. (2020). Multigene phylogeny and taxonomic revision of Atheliales s.l.: Reinstatement of three families and one new family, Lobuliciaceae fam. nov. Fungal Biology.

Tedersoo, L., May, T. W., & Smith, M. E. (2010). Ectomycorrhizal lifestyle in fungi: Global diversity, distribution, and evolution of phylogenetic lineages. Mycorrhiza, 20(4), 217–263.

Links

So byssoid and blue! This species also acquires yellow patches, perhaps as it ages.

The color of Byssocorticium atrovirens derives from the blue-green hyphae.

The hyphae are long and branching at right angles with a rough, course texture. In this photo, a glob of gunk can be seen on a hypha in the center.

The spores are small and subglobose with a pointy apiculus that gives them the appearance of a pear. Note the large oil droplet (guttule) in most spores.

The basidiospores of Byssocorticium atrovirens are cyanophilic, meaning they stain dark blue in cotton blue mounting medium.

The basidia have four sterigmata (although these appear to have two) and are often filled with guttules.

This is the beginning of a finger-like hyphidia. While the subicular hyphae completely lack clamps, the subhymenial hyphae have occasional clamps, distinguishing this species from Byssocorticium efibulatum.

Another look at the distinct finger-like a hyphidia, a characteristic also reported for a different genus in the family, Tretomyces.

Byssocorticium ITS maximum likelihood phylogenetic tree. The sequences were aligned in SeaView with MUSCLE, trimmed with TrimAl, and analyzed with RAxML using 1000 bootsrap replicates and the GTR+G model. Sequences are annotated with their GenBank accession number and location of origin. Bootstrap values ≥ 70% are considered significant. Leptosporomyces galzinii serves as the outgroup.