Peniophora cinerea (Pers.) Cooke

Introduction

Peniophora cinerea is a common, cosmopolitan crust that grows saprotrophically primarily on medium sized deciduous branches. As a powerful white-rot fungus, it has been the target of bioprospecting for laccases (enzymes that degrade lignin) to decolorize textile waste water (Moreira et al. 2014). Peniophora cinerea is surprizingly is difficult to work with under the microscope due to its thin hymenophore and dense, agglutinated subicular hyphae. These traits appear to be an adaptation to its xeric habitat on suspended branches. Cross sections are unsquashable and result in many broken coverslips. I recommend shaving very thin bits off the top, letting them soak, and then squashing thoroughly to get a side-angle view of the microstructures. The encrusted lamprocystidia are abundant and interesting. I don't think their function is known, but I'd guess they are also an adapatation to this crust's particular habitat.

Early on, Peniophora cinerea was the focus of detailed taxonomic studies based on mating tests and DNA sequence similarity. Chamuris (1991) reported sterility barriers between European isolates based on substrate, suggesting incipient sympatric speciation, but Hallenberg and Larsson (1992) later discovered a European strain that linked the two groups, and all populations succesfully crossed with North American and Asian isolates. According to the biological species concept, which says that two individuals or populations belong to the same species if they can succesfully reproduce, this is evidence that Peniophora cinerea is a "good" species with a widespread distribution. In 1996, Hallenerg et al. used ITS2 rDNA sequences of Peniophora spp. to construct what must have been one of the earliest sequence-based phylogenetic trees for non-model fungi. I commend these pioneers who were so limited by technology that routine procedures like bootstrap analysis were not feasible because their dataset, which contained 65 sequences, was too large.

Description

Ecology: Growing on the underside of a fallen hardwood branch.

Basidiocarp: Effused, adnate, beginning orbicular, becoming confluent, membranaceous to coriaceous, grey to pale grey (pale mouse grey), extensively cracked (rimose); hymenophore smooth to tuberculate, thin; margin narrowly fimbriate, pale grey, adnate or peeling up taking the surface bark layer with it.

Chemica reactions: Ammonia, iron salts, and potassium hydroxide result in a dark greyish black reaction.

Spore print: NA

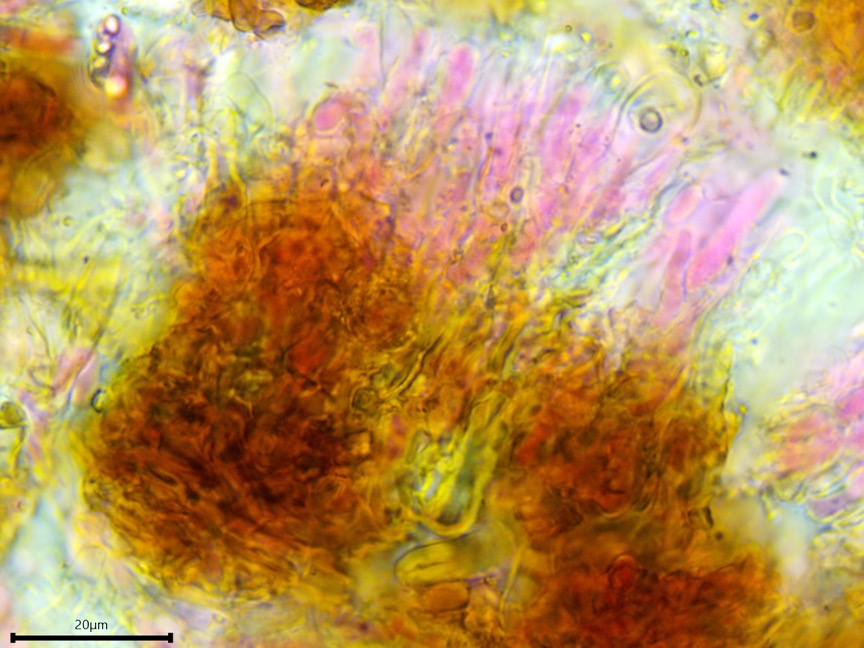

Hyphal system: Monomitic, subhymenial hyphae vertical, supposedly clamped (but difficult to discern), subicular hyphae dense, brown, possibly thick-walled.

Basidia: Difficult to find (although spores were abundant), approximately 30 ✕ 5.5 µm with four long sterigmata.

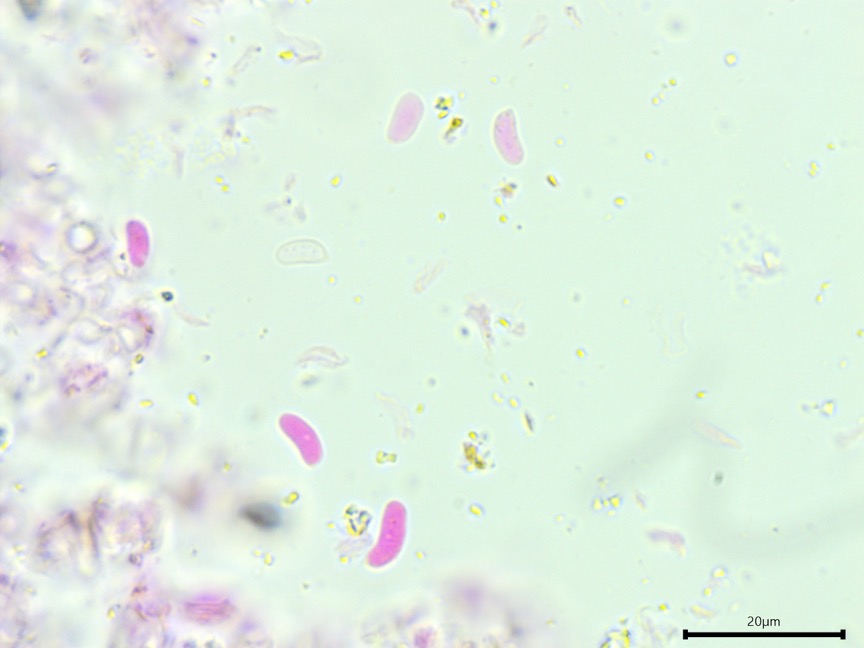

Basidiospores: Narrowly cylindrical, straight to curved, smooth, thin-walled, inamyloid; length (6.3) 6.9–8.2 (9.4) µm, width (2.9) 3.0–3.7 (4.3) µm, x̄ = 7.6 ✕ 3.3 µm, Q (1.6) 2–2.6 (2.9), x̄ = 2.3 (n = 30).

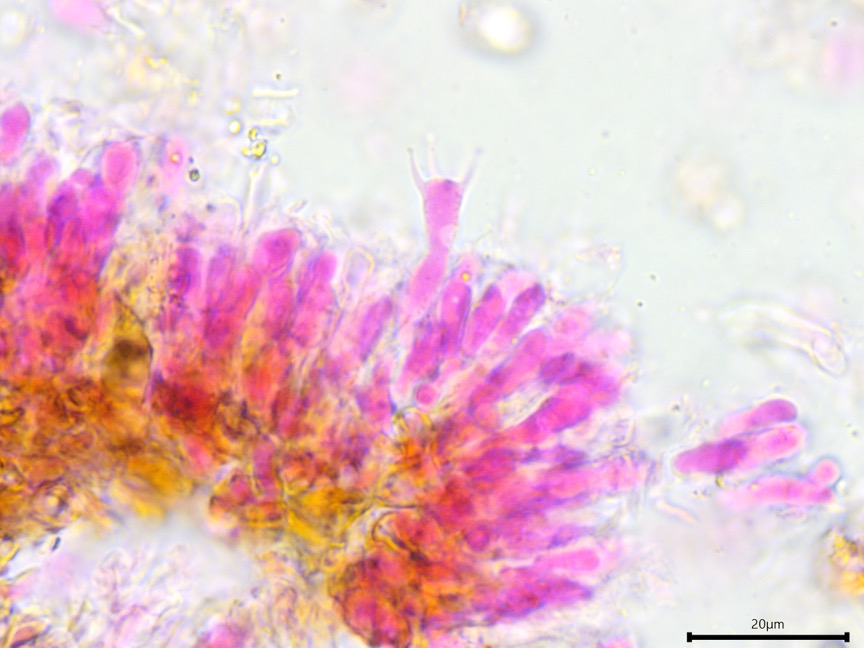

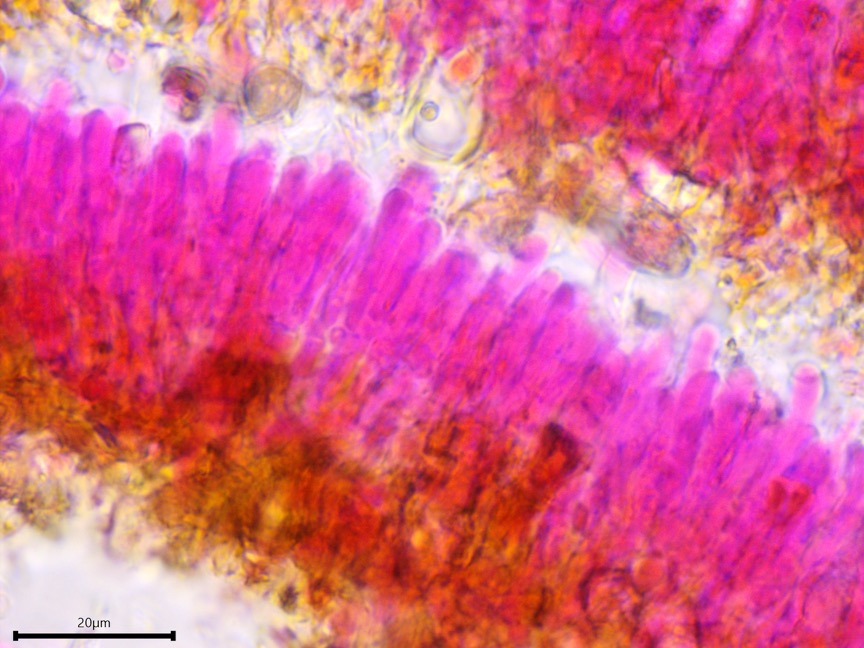

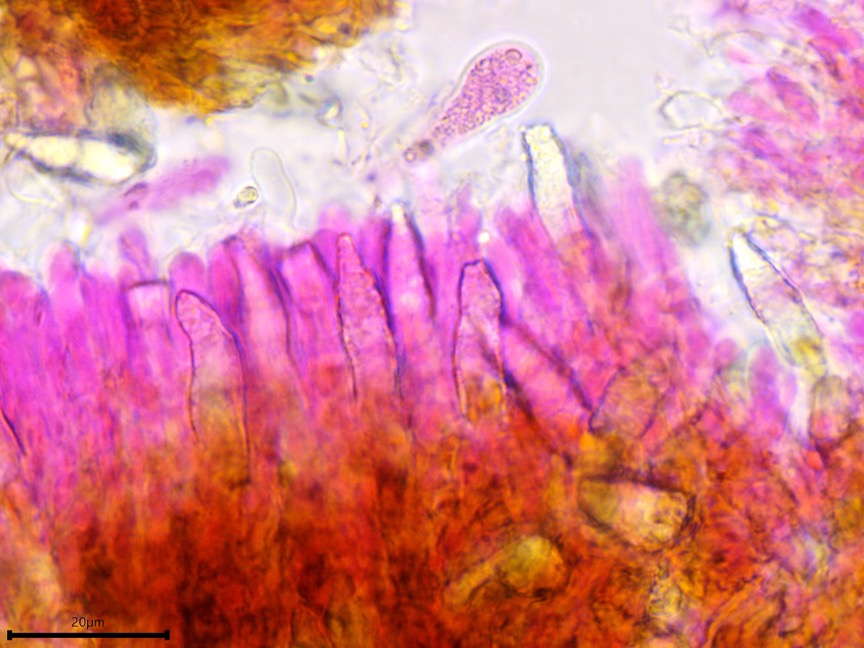

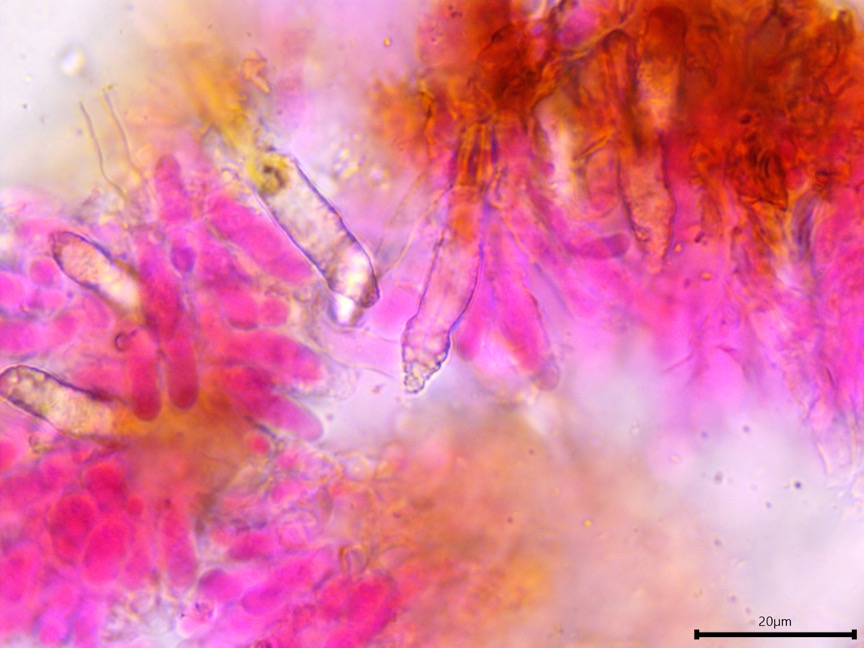

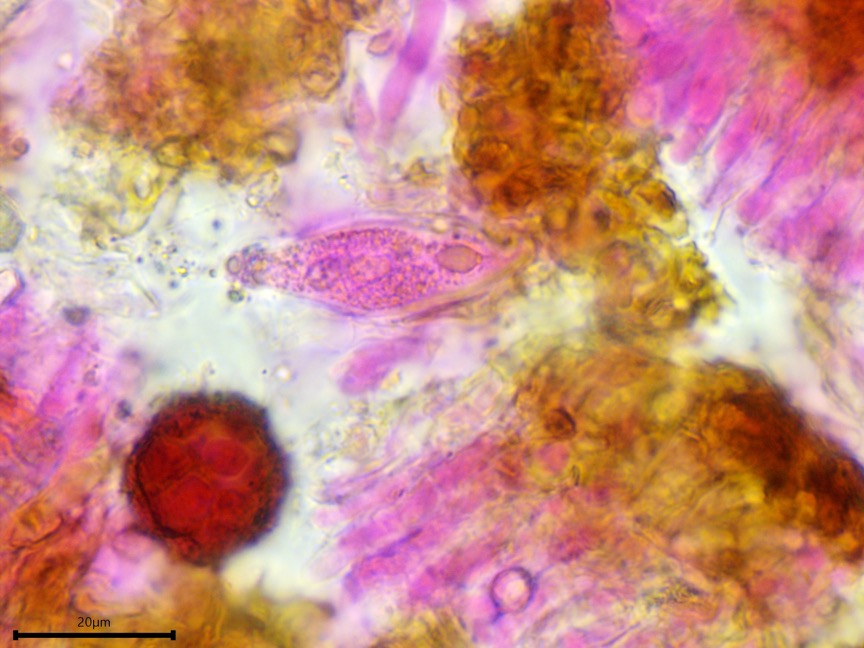

Sterile structures: Lamprocystidia very abundant, basal part brown and thick-walled with a thin lumen, apical part encrusted, apparently not dissolving in 5% KOH, torpedo-shaped or conical; length (23.8) 28.7–41.2 (44.3) µm, width (5.5) 5.8–7 (7.5) µm, x̄ = 34.9 ✕ 6.4 µm (n = 10). Gloeocystidia present but infrequent, filled with granular content, vesicular, ovoid, or fusoid, thick-walled; length almost identical to the lamprocystidia but slightly wider, (9.7) 9.8–12.7 (13.7) µm, x̄ = 11.2 µm (n = 7).

Sequences: NA

Notes: All measurements taken in 5% KOH stained with phloxine B. Andreasen and Hallenberg (2009) state that gloeocystidia are absent or indistinct in the Peniophora cinerea group. The gloeocystidia observed in this specimen were distinct, but only a few were found, all of which were localized to a small section of the squash mount. The lamprocystidia were slightly bigger than what is reported for Peniophora cinerea and may actually match Peniophora spathulata better, although this species is suspected to be synonymous with Peniophora cinerea and has only been documented in Taiwan (Andreasen and Hallenberg 2009).

Specimens Analyzed

ACD0381, iNat62862820; 17 October 2020; Nan Weston Preserve, Washtenaw Co., MI, USA, 42.1859 -84.1110; leg. Alden C. Dirks, det. Alden C. Dirks, ref. Andreasen & Hallenberg (2009); University of Michigan Fungarium MICH 352289.

References

Andreasen, M., & Hallenberg, N. (2009). A taxonomic survey of the Peniophoraceae. Synopsis Fungorum, 26, 1–48.

Chamuris, G. P. (1991). Speciation in the Peniophora cinerea complex. Mycologia, 83(6), 736–742.

Hallenberg, N., & Larsson, E. (1992). Mating biology in Peniophora cinerea (Basidiomycetes). Canadian Journal of Botany, 70(9), 1758–1764.

Hallenberg, N., Larsson, E., & Mahlapuu, M. (1996). Phylogenetic studies in Peniophora. Mycological Research, 100(2), 179–187.

Moreira, S., Milagres, A. M. F., & Mussatto, S. I. (2014). Reactive dyes and textile effluent decolorization by a mediator system of salt-tolerant laccase from Peniophora cinerea. Separation and Purification Technology, 135(1), 183–189.

Links

JGI MycoCosm (Peniophora aff. cinerea genome)

Peniophora cinerea has a "pale mouse grey" color.

The hymenophore is distinctly rimose, or cracked, in age.

Peniophora cinerea begins orbicular and then becomes confluent as it grows across its substrate. Notice the very thin, pale grey, fimbriate margin.

Chemical reactions: (left to right) ammonia, iron salts, and KOH.

Narrowly cylindrical basidiospores.

Lone basidium.

Suspected clamp connection. Can you find it?

The subicular hyphae are dense, brown, agglutinated, and possibly thick-walled.

Lamprocystidia and gloeocystidia.

Lamprocystidia.

Gloeocystidium.