Protomerulius minor (Möller) V. Spirin & O. Miettinen

Introduction

If you encounter a crust with septate basidia, there's good news and bad news. The good news is that your options dwindle considerably to species in Auriculariales, Cantharellales, and Sebacinales (assuming it's not actually a jelly in Dacrymycetes or Tremellomycetes). The bad news is that these are all difficult orders to work with and no comprehensive keys exist for species-level identification.

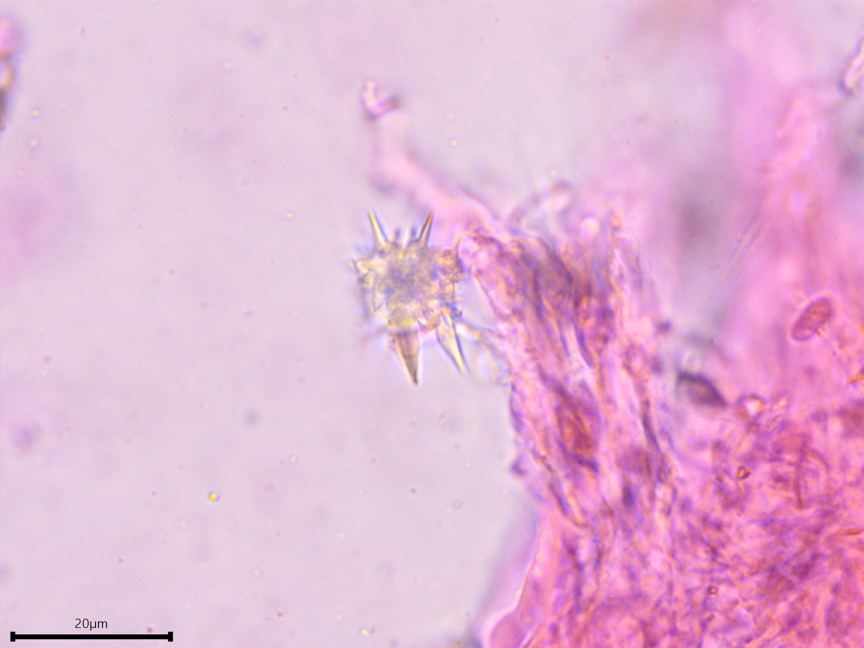

Given that I am inexperienced with heterobasidiomycetes and the go-to general crust references do not treat them at all, I was initially helpless in identifying this specimen even to order level. Then, browsing through Elia Martini's extraordinary illustrations, I just happened upon one that I knew instantly to be a lead: Protomerulius dubius. The drawings of the spiky balls were a dead ringer for what I was seeing, and I learned from Spirin et al. (2019) that the presence of these crystals is a defining morphological feature of Protomerulius crusts. Crystals appear in such diverse forms across so many crusts. Why does one species coat its hyphae in sharp needle crystals or blocky chunky ones, another produce crystal enshrouded lance-shaped cystidia, and yet another make giant spiky balls? The chemical control of these fungi over the growth of crystals is exquisite, but to my knowledge we have no idea how or why they do this.

Like many crusts, we know basically nothing about this species except for its taxonomy and morphology. Protomerulius minor appears to be widely distributed in the Americas, from Brazil northwards to the United States. Stypella minor is a synonym.

Description

Ecology: Growing on the underside of a brown-rotted hardwood log; the nutritional mode of this species is unknown.

Basidiocarp: When young, whitish to cream-colored, later greyish to ochraceous; hymenophore effused, smooth to finely reticulate or minutely granulose (described as "more or less regularly hydnoid" by Spirin et al. (2019)), pruinose to byssoid (floccose) to subceraceous in texture; margin indeterminate, gradually thinning out.

Chemical reactions: NA

Spore print: White.

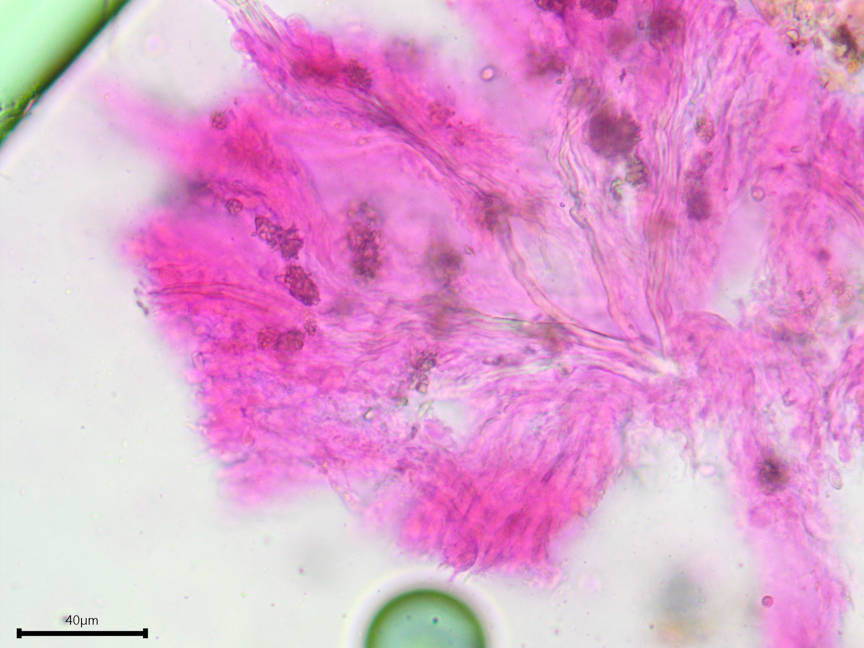

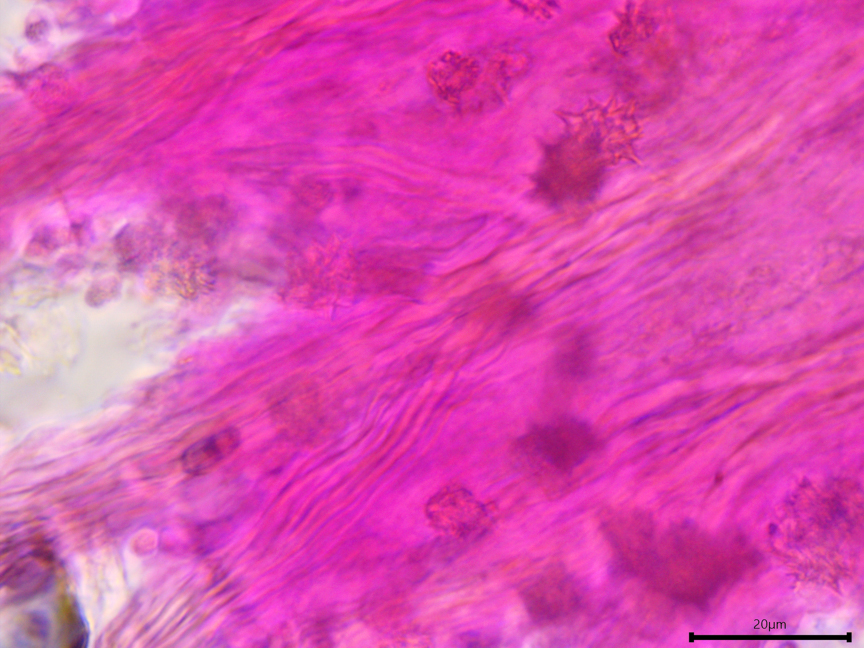

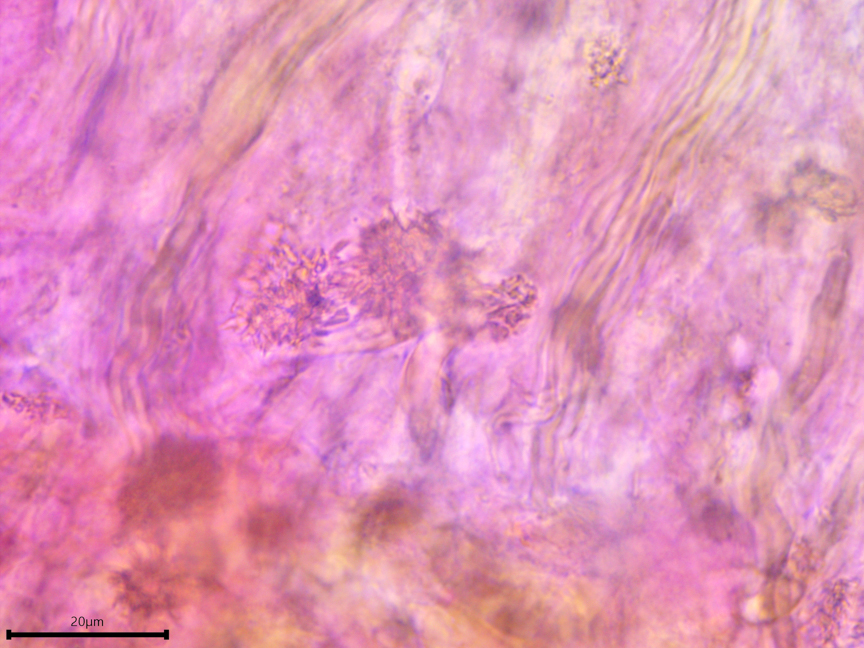

Hyphal system: Dimitic, with skeletal hyphae; generative hyphae reported as clamped, but very difficult to observe; very prominent and characteristic (for the genus) spiky crystal balls (stellate agglomerations) present throughout the basidiocarp, up to 24 µm across.

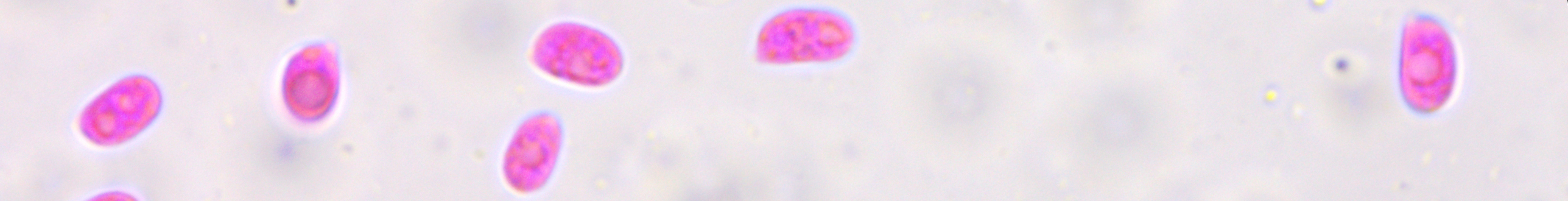

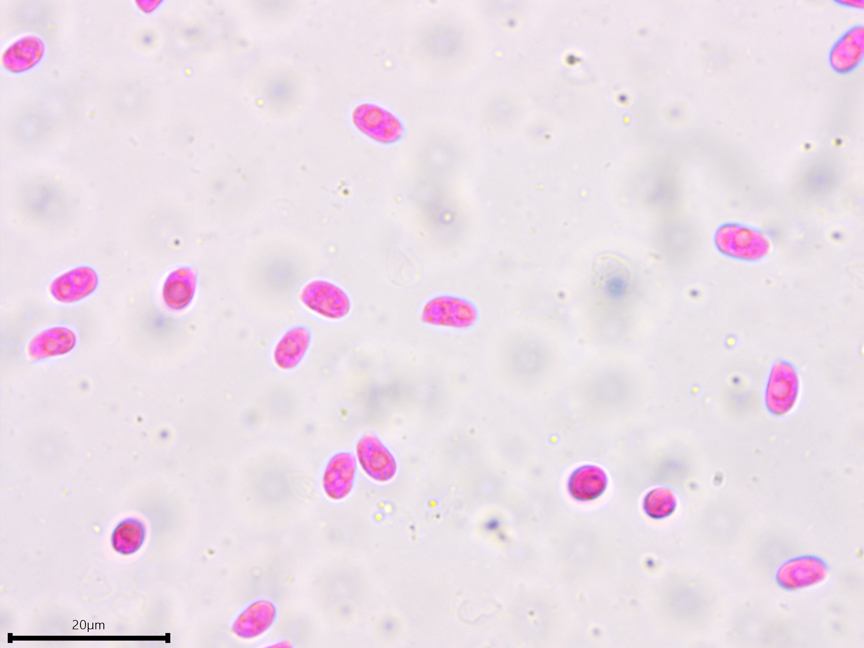

Basidia: Cruciate (longitudinally septate heterobasidia), sphaeropedunculate (ellipsoid to subglobose basidia with a stalk), with two to four sterigmata depending on the number of cells per basidium; length (9.2) 9.7–12 (13) µm (length may include stalk, difficult to differentiate), width (5.6) 5.9–7.4 (7.9) µm, x̄ = 10.8 ✕ 6.6 µm; sterigmata length (3.7) 4.8–8.2 (9) µm (n = 10 basidia and 10 sterigmata).

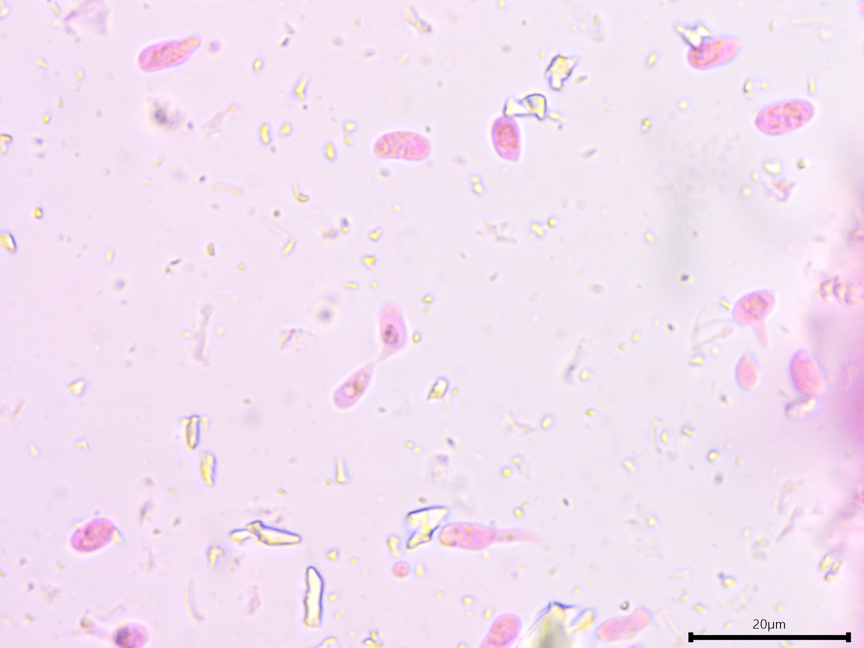

Basidiospores: Ellipsoid to cylindrical with a flattened adaxial side, smooth, thin-walled, inamyloid, acyanophilous, repetitive; length (6) 6.3–7 (7.5) µm, width (3.7) 3.9–4.2 (4.4) µm, x̄ = 6.6 ✕ 4.1 µm, Q (1.5) 1.5–1.7 (1.9) (n = 30 basidiospores).

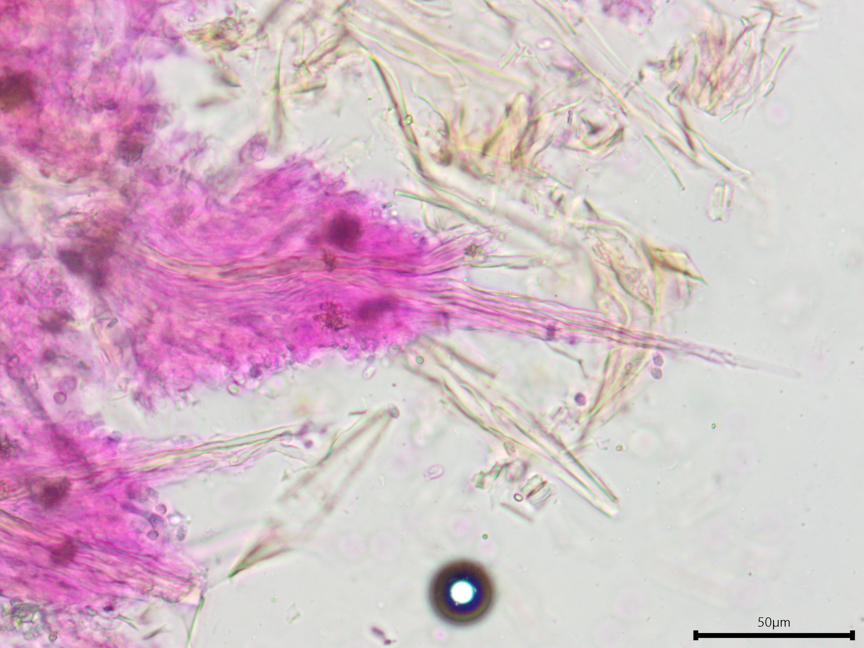

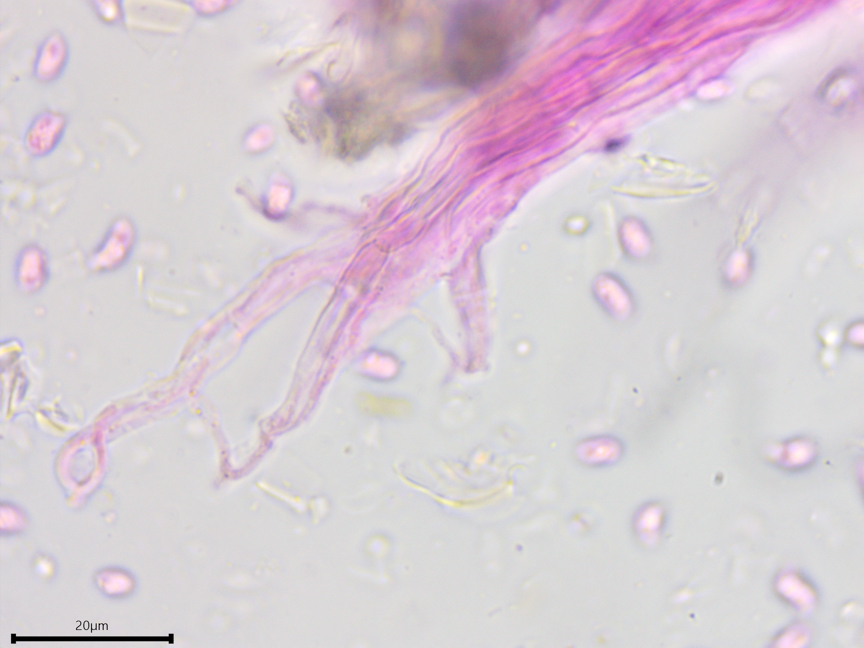

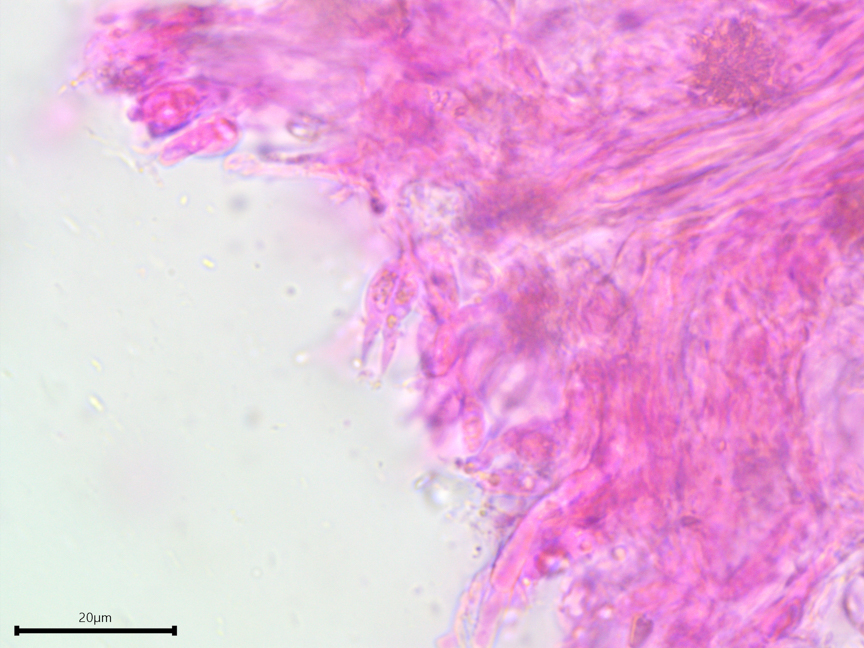

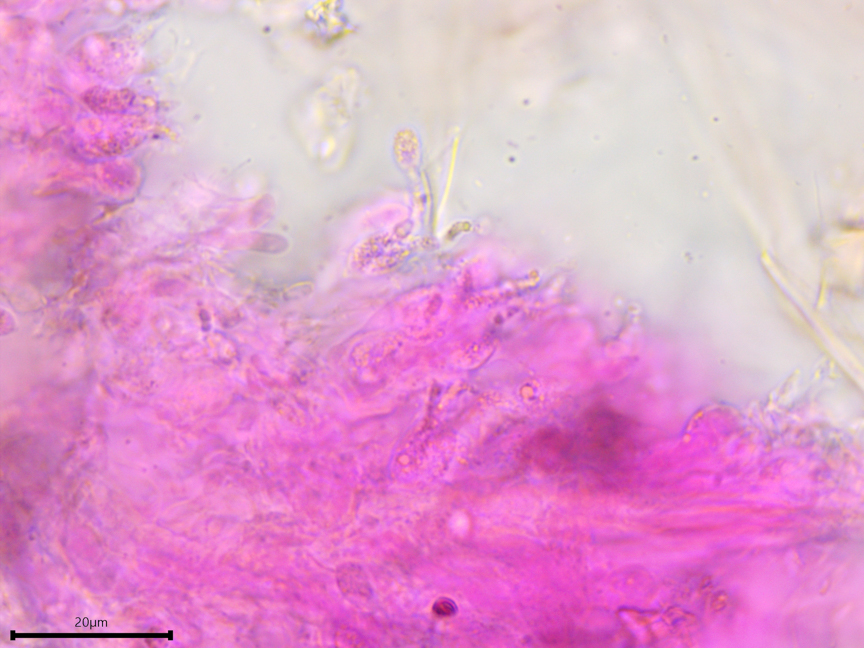

Sterile structures: Thick-walled pseudocystidia (tramal cystidia) arising from the skeletal hyphae, typically wrapped around each other and bundled together in fascicles as they project beyond the hymenium in the center of minute "teeth" or mounds (giving the basidiocarp its granulose to hydnoid appearance), becoming thin-walled and sometimes tapering at the apex and forming bristle-like tips; up to hundrds of microns long, width 3.0–4.5 (5.9) µm (n = 10 cystidia).

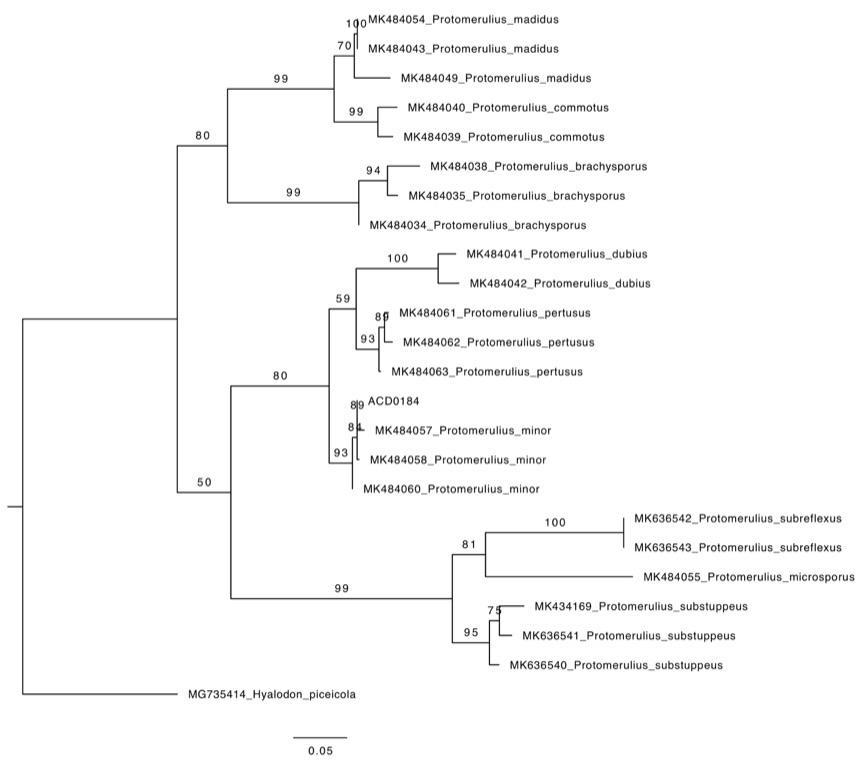

Sequences: ITS rDNA (MZ919178).

Notes: All microstructures were measured in 5% KOH stained with phloxine B. I originally identified this specimen as Protomerulius dubius, a European species, but sequence data appropriately confirmed that this was the American Protomerulius minor.

Specimens Analyzed

ACD0184, iNat33478375; 24 September 2019; Ann Arbor, Washtenaw Co., MI, USA, 42.2951 -83.7243; leg. & det. Alden C. Dirks, ref. Spirin et al. (2019); University of Michigan Fungarium MICH 352189.

References

Spirin, V., Malysheva, V., Miettinen, O., Vlasák, J., Alvarenga, R. L. M., Gibertoni, T. B., … Larsson, K. H. (2019). On Protomerulius and Heterochaetella (Auriculariales, Basidiomycota). Mycological Progress, 18(9), 1079–1099.

Links

Protomerulius minor on the underside of a log with brown rot.

Young basidiocarps are whitish, creamy, or ochraceous in color.

The basidiocarp is subceraceous when young and fresh with a granulose apperance, which is a result of the crust growing over an uneven substrate and also the presence of miniscule mounds.

A look at the hymenophore, consisting of thick-walled pseudocystidia arising from skeletal hyphae. The trama is embedded with spiky crystal balls.

Bundled pseudocystidia.

While most pseudocystidia have regular hyphal ends, some narrow into frayed-looking, hyphidial tips.

A closer look at the bundled pseudocystidia and embedded crystal balls

Origins of the pseudocystidia.

Spiky crystal ball.

Longitudinally septate basidium.

Basidia at the base and sides of a pseudocystidia fascicle.

Basidiospores.

An example of a repetitive basidiospore growing a sterigma and a second basidiospore.

Phylogenetic tree of ITS rDNA sequences from the studied specimen and selected vouchered specimens from Spirin et al. (2019). The sequences were aligned in SeaView with MUSCLE and made into a tree with RAxML using 100 bootsrap replicates and the GTRGAMMA substitution model. Hyalodon piceicola serves as the outgroup.